I’m Rob Lockhart, the Creative Director of Important Little Games. If you were to follow me on twitter, I’d be grateful.

<(╯°□°)╯·._.·´¯)·._.·´¯)

I’m working on a game that involves magic and magical epistemology. Consequently, I’ve been doing a lot of research about magical systems. I’d like to describe a few here, for those of you interested in incorporating magic into your games. One of the things I think games is best suited to, is to give a person the feeling of being able to do something impossible. What could be more impossible, or more satisfying, than the ability to use magic? I hope that this post will inspire you to create interactive systems of magic that are amusingly unique and uniquely amusing.

Harry Potter & The Lord of the Rings (& Naruto)

I love Harry Potter and the Lord of the Rings series both, but they share a sloppy dismissive view of magic. If I were going to try to attempt to answer questions about how magic works in the universes these works of fiction take place, I’d be hard pressed for a place to start. There seem to be spells for all kinds of things available in various arcane languages, but with very little discernible pattern as to how the spells are constructed. Magical items, too, might answer to any description, and can have arbitrary powers.

J.R.R. Tolkien, J.K. Rowing and Masashi Kishimoto are great writers, so they don’t use spells or items as deus-ex-machina. Every spell or item is well introduced to the reader before it can have an impact on the plot. Nonetheless, the lack of a coherent mythology which explains the workings of magic invites this kind of abuse of narrative form, and less skilled writers who try to emulate these authors or who work in a similar milieu have trouble pulling out a previously unheard-of magical trick when it is convenient for the story.

In a way, it is unfortunate that J.R.R. Tolkien was so influential to Gary Gygax, and that Gary Gygax has had such a huge impact on video games. This kind of disordered free-for-all view of magic makes the enjoyment of many games (such as WoW) dependent upon memorization (or constant reference), in some measure, for their full enjoyment.

Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell

In this novel, magic was an art lost to time, except for a few obscure references scattered across a few hundred rare and otherwise un-entertaining books, so it would be excusable for the magic to be just as chaotic as in LOTR, since the characters only have a small piece of an established body of knowledge. In fact, it does seem this way for most of the novel’s length.

Near the end, however, a bit of coherence is added when Mr. Strange is granted nearly limitless power. He merely speaks to the objects in nature in their own language, and they obey. This is an element of magical fiction I like to call the “Language of Nature.” While not being a perfect explanation for how magic is allowed to influence the world within the fiction, it at least provides a distinct path to mastery — to learn magic, you must learn this language. This also implies that the elements of nature have a a degree of consciousness; at least enough to understand a (presumably unconstructed, aka natural) language, and obey.

This also helps one of the important narrative conundrum in any fictional universe that includes magic: ‘why can’t everyone use magic all the time?’ In this case, the answer is that the language is largely forgotten, or (even better) it is extraordinarily difficult to master.

This brings to mind the general principle, shared by many conceptions of magic, that symbols can have a direct influence on the world (other than via the human mind). In truth, it seems that the ‘language of nature’ seems to be Mathematics, but it’s a language nature only speaks but doesn’t understand. This must have frustrated even the earliest people making systematic observations of nature. While numeracy and symbols have so much explanatory power, they have no power whatsoever to influence the things they describe. But what if…

click the image for artist’s page

A Wizard of Earthsea

‘A Wizard of Earthsea’ and its follow-up novels have a similar conceit. In order to command the forces of nature, one must know the true name of the thing one is trying to command. That name, such as the name referring to the wind, can also change regionally, so a wind over the Pacific might have a different name than the winds over the Atlantic. Simply knowing the name seems to be enough to summon a thing, like summoning a hawk out of the sky, one of the earliest bits of magic the main character, Ged, is able to accomplish.

The Name of the Wind

This book, as the title suggests, also includes the concept of the power of names. It also includes descriptions of a lesser form of magic known as Sympathy.

In sympathy, the magic user must form the firm belief that two entities are linked, and then they become so. This is another theme quite common in magical mythology: mind over matter. One’s state of mind is an important component of many magical practices, whether it be perfectly calm, fiercely effortful, or, in this case, utterly credulous.

Once linked, entities may have a sort of positional entanglement, or may be able to transfer heat at a distance, or change heat from one into kinetic energy in the other, etc. Sympathy also introduces the idea that a sympathetic link’s efficiency depends on the similarity and provenance of the two linked entities. For example, two apparently identical coins will be easier to link than two coins of different denominations. Personally, I think this is a very clever concept, which puts firm limitations on the performance of this kind of magic, while still allowing miraculous things.

Sympathy has its own explanations for why magic is uncommon. Here, creating this unshakable belief of a known falsehood is a near-impossible mental exercise. In addition, performing most useful magic involves a Rube Goldberg-esque set of complex interconnections between various things.

Sympathy also preserves quite a lot of laws of nature, including conservation of energy. For instance, a character might light a candle by linking the wick to her own body, drawing heat from herself, but this will make her very cold very fast.

Fullmetal Alchemist

This manga and anime series also preserves quite a lot of laws of nature – notably conservation of mass. This is known in the lore of this series as the “Law of Equivalent Exchange.” It also states that you can’t transmute something from one material to another. However, alchemists who know the proper runes and transmutation circles are able to alter the form of physical matter however they see fit.

There is also an exception to the Law of Equivalent Exchange. If an alchemist is in physical contact with a crystalline material known as a Philosopher’s Stone (which can only be crafted using the blood of thousands of dead people), their transmutations need not obey Equivalent Exchange. This makes Philosopher’s Stones so valuable that people are routinely willing to commit mass murder to obtain them.

Here is another concept common to many ideas of magic: physical contact. In real-world physics, physical contact has no real definition. At the scale of fundamental particles, messenger particles are being exchanged in order to repel clouds of electrons from one another. The same is true for every set of two materials, and even within materials – there is little difference in the process of atoms nearing one another. The idea of a discrete ‘object’ or of ‘touching’ that object are telltale signs of a pre-20th century model of nature. Nonetheless, from a commonsense perspective, the idea of losing or gaining some ability while touching or holding a special object still has rhetorical power.

Mistborn

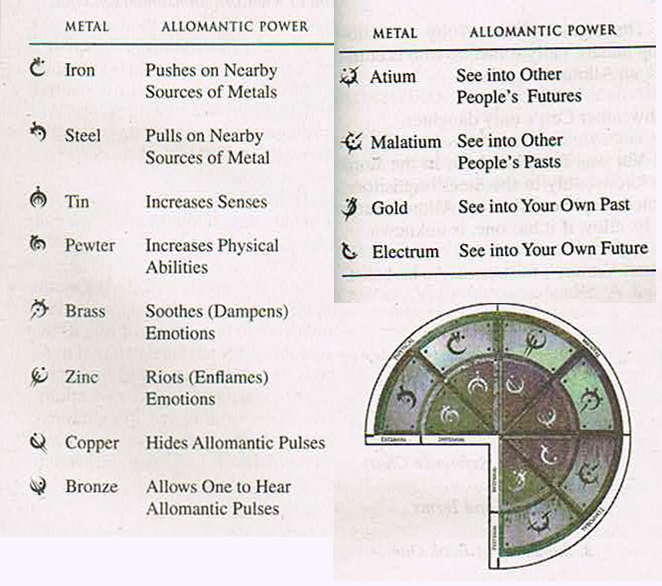

Brandon Sanderson’s novels introduce a fascinating form of magic. In his universe, there exist three forms of magic, but the one I’ll describe here is the most ingeniously crafted, and clearly the basis for the rest. Allomancy is the rare genetic ability to ‘burn’ metals in order to gain specific powers. Most allomancers can only burn one kind of metal, granting them one supernatural power. A few, called Mistborn, can burn all the allomantic metals. An appendix in the back of each of the books explain the workings of each of the metals:

Twelve of the 16 metals.

This power comes with a lot of limitations (assuming you possess it at all). You must ingest the correct metal, which means you have a finite supply. Someone burning bronze can locate other allomancers, unless they or someone nearby is burning copper.

The whole system is very balanced and rational, which is part of what makes this series so thrilling. Grasping the full extent of the powers available takes very little time, so it becomes a game of how to use and combine these skills in novel ways.

The Last Airbender

In the Nickelodeon cartoon series “Avatar: The Last Airbender,” magic is a unique skill which is randomly granted to a small percentage of the population. Furthermore, the world is ethnically and geopolitically divided into four parts: Earth, Air, Water and Fire. Likewise, the magical system is divided: Earthbending, Airbending, Waterbending and Firebending. People from the Fire Nation, for instance, are only granted the ability to Firebend, if any.

All these types of ‘bending’ require a source of the material in question, so waterbenders are powerless in the desert (unless they bring their own water, which would be wise). And manipulation of the material is done through special gestures, as well as a little mind over matter. This introduces the new concept of body motions as magical symbols.

In this lore, only one person in the world can do more than one kind of bending — the Avatar, who must master all four.

Sabriel

In the Abhorsen trilogy, there are a few kinds of magic. The most common is Charter magic, which involves bringing your conciousness into another plane with runes that flow like a river through it. Practitioners of charter magic, called ‘charter mages’ must pluck these runes from the flow and bring them into the material world, where they assemble spells like recipes. This brings up the interesting notion of symbols taking physical form. This is common in many supernatural anime, such as Fairy Tail and Strait Jacket.

There is also free magic, which has a sort of wildness and unpredictability to it. Necromancers command one form of free magic which has its own schema involving seven bells. The bells can be used in life, but are most effective when traveling into the seven precincts of death – a process which, from the outside, looks like someone voluntarily going into a coma or trance. Here, sounds are symbols, and even sometimes have a rough equivalency to charter runes.

Codemancer

Codemancer is a fantasy video game I’m working on in which magic is code. Players write ‘spells’ (programs) and then ‘cast’ (run) them. This is a variation on the “Language of Nature” with a hint of mind over matter. In this case, the language of nature is so specifically defined that it doesn’t require a human-level of intelligence to understand it, just a simple computer-level intelligence.

You can see a bit about how the magic works in this youtube video.

As game developers, my opinion is: the more logical the magical systems in our games, the better. A logical magical system drastically decreases the learning curve of the game, and may decrease development time as well. I’ve found that it’s especially satisfying if players can stack or combine a few abilities in novel ways, and to master these combinations, before new ones are introduced. If enemies abilities fall within the same logical system, then so much the better. Enemies who must act within the same constraints (even if given more power to work with) increases our sense of fair play, which is a fragile thing.

I hope you’ve enjoyed this first round of magical systems. Stay tuned for part 2!